|

Malcolm Lubliner ~ Photography & Art Since 1965 |

| Historic Mexico | About Historic Mexico | Photographs Page 1 | Photographs Page 2 |

"Castle

Guanajuato" |

||||||||||||

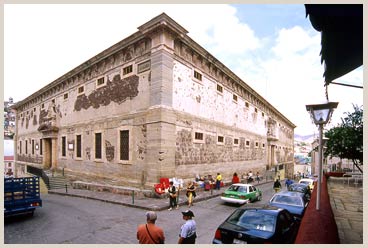

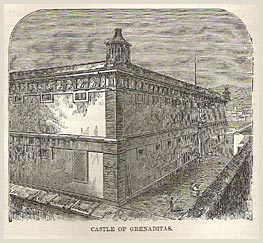

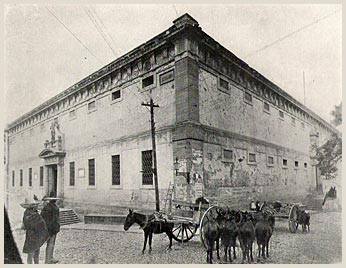

In 1786 the Spanish crown ordered that New Spain be divided into 12 provinces. One of those provinces was Guanajuato. The third provincial governor of Guanajuato was Juan Antonio de Riaño y Barcena. It was he who began the construction of the storehouse which George P. Thresher labeled “Castle Guanajuato” but which is more formally known as the “Alhóndiga de Granaditas”. The construction was initiated in 1798 and the Alhóndiga wasn’t completed until 1809, just before the Mexican fight for independence from Spain began. It must have been a massive construction effort at the time. On September 16, 1810 Padre Miguel Hidalgo ignited the fight for independence at the nearby town of Dolores and the Spanish troops and authorities at the town of Guanajuato took refuge from the revolutionaries in the newly constructed and seemingly impregnable Alhóndiga.

The Alhóndiga of Guanajuato is one of the most famous historic sites in Mexico and has a special place in Mexican history. It was here that the first major blood was spilled for the cause of liberty and it was during this fight that one of the most endearing figures of Mexican history emerged. Every Mexican school child knows the story of “El Pípila” (pronounced ehl PEE-pee-lah). When the Spaniards barricaded themselves inside the Alhóndiga they felt safe from harm and they hurled murderous fire down upon the freedom fighters with their muskets and the insurgents suffered much loss of life and limb until El Pípila stepped in to save the day. He strapped a big flat rock on his back to protect himself from the musket fire and crawled up to the great wooden doors of the Alhóndiga where he set them ablaze with the help of a type of wood called “ocote” (oh-KOH-teh) or what in English is known as “pitch pine”. When the doors burned away the freedom fighters eventually gained entry and slaughtered all of the Spaniards within. El Pípila was the hero of the day and still retains a special place in the heart of every Mexican.

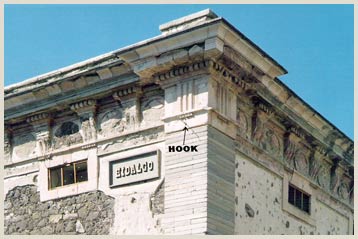

The real name of “El Pípila” was Juan José de los Reyes Martínez Amaro. He received his nickname “El Pípila” from his companions on account of his pockmarked face. The word “pípila” means “turkey egg” in his native language and anyone who is familiar with turkey eggs can tell you that they are mottled and have a rough surface. He was born in San Miguel de Allende on the third of January in 1782 and he died in Guanajuato on the 25th of July 1863. He worked in a mine called “Mellado” which is near to Guanajuato. There is a large monument to El Pípila overlooking the City of Guanajuato and a statue of him at the main entrance to the City of San Miguel de Allende. Not long after the fight for independence Padre Miguel Hidalgo was captured by the Spaniards and executed. His corpse was decapitated and they put his head in a wire cage and suspended it from a hook located on the top outside corner of the Alhóndiga. It hung there for 13 years until the fight for independence was won and from the other three corners hung the heads of his fellow patriots, Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, and Mariano Jiménez.

In 1864 Maximilian visited Guanajuato and declared that the Alhóndiga be turned into a prison and it remained a prison until the early 1950’s when it was restored to its original glory and is now a museum. To this day, however, you can still see the hook from which hung the head of Padre Hidalgo. Colonel Albert S. Evans who visited the Alhóndiga in 1869 with William S. Seward, the former U.S. Secretary of State, described the prison this way: “There were about three hundred men and boys and thirty-six women in the Carcel [jail]. They were in apartments containing from twelve to twenty-four each, all opening on the great courtyard, and light and well ventilated. They were working at boot and shoe making, weaving serapes and coarse blankets, making tallow candles, etc., etc., or attending school.” Harry A. Franck visited the Alhóndiga in 1915 and encountered more or less the same thing. This is what he had to say about it in his book “Tramping Through Mexico”: The walls once red with the blood of Spaniards slaughtered by the forces of the priest of Dolores had lost that tint in the century since passed, and were smeared with nothing more startling than a certain lack of cleanliness. The immense, three story, stone building of colonial days enclosed a vast patio in which prisoners seemed to enjoy complete freedom, lying about the yard in the brilliant sunshine, playing cards, or washing themselves and their scanty clothing in the huge stone fountain in the center. The so called cells in which they were shut up in groups during the night were large chambers that once housed the colonial government. By day many of them work at weaving hats, baskets, brushes, and the like, to sell for their own benefit, thus being able to order food from outside and avoid the mess brought in barrels at two and seven of each afternoon for those dependent on government rations. Now and then a wife or feminine friend of one of the prisoners appeared at the grating with a basket of food”. Later Mr. Franck goes on to say: “There were all told, some five hundred prisoners”.

One final word about El Pípila. Although it is currently in vogue to cite Juan José de los Reyes Martínez Amaro as the one and only original Pípila there seems to be a bit of controversy among historians over that point. In fact, many of the sources that I have read describing the Alhóndiga as seen over the years and up until about the 1930’s or until the monument to Pípila was built overlooking Guanajuato, say that the name of the peon who strapped the rock to his back and set fire to the doors of the Alhóndiga was unknown. Historian Joseph H.L. Schlarman in his book “Mexico, Land of Volcanoes” (Bruce Publishing, Milwaukee, 1950) says that a “group of miners” protecting themselves with stones set fire to the doors. From about 1900 until about 1950 many visitors mention seeing a statue of a peon with a rock slab on his back inside the corridor of the Alhóndiga prison protected by iron bars but it seems to have since disappeared and no one can say for sure where it is. In reading accounts of the Pípila story written over the years one encounters names such as “José Maria Barajas of Dolores and Mariano Bernal of Taxco, among others, who were also purported to be El Pípila. In the end, however, it really doesn’t matter whether Pípila was one man or many men who helped ignite the doors to freedom and independence for the Mexican people. The Spirit of Pípila is still alive and well and waiting in the wings for the next Alhóndiga to conquer. |

||||||||||||

| Home | Nature & Human Nature | Automotive Landscape | Artists Portraits | Historic Mexico | Resumé | Contact |