|

Malcolm Lubliner ~ Photography & Art Since 1965 |

| Historic Mexico | About Historic Mexico | Photographs Page 1 | Photographs Page 2 |

"Teatro

Juárez" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

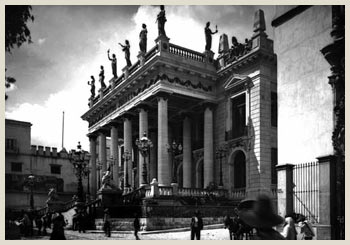

To correctly tell the story of G.P. Thresher’s photo “Theatre at Guanajuato” or what is more commonly known as “Teatro Juárez” one must first tell the story of what came before. The site of the theatre is actually two sites in tangent, one secular, and one religious, and they march through history together like inseparable twins. The religious site was born first. About 100 years after the city of Guanajuato was founded it was still without a local “convento” or what we would normally call a monastery. For this reason, in the year 1663 a small group of Franciscan Friars came to Guanajuato and on the 22nd of January celebrated mass for the first time in a tiny chapel improvised from tree branches. They didn’t receive permission from the Spanish government to found their mission, however, until the 29th of March in 1677 but by then they had gotten into a squabble over real estate with one of their neighbors. That issue wasn’t resolved until 1679. From that date begins the real story of the church of San Pedro Alcantará and the convento of San Diego Alcalá. San Diego Alcalá was a favorite patron saint of the branch of the Franciscan order known as Dieguinos. He was born in the year 1400 and died in 1463. San Diego, California is named after this saint primarily because the city was founded as a mission by Padre Junipero Serra who was also a Franciscan. San Pedro Alcantará was the founder of the Dieguino branch of the Franciscan Order and San Pedro Alcantará and San Diego Alcalá are often confused with one another but I really don’t think they would mind. The order is sometimes also called the Alcantarinos or the Franciscans “Descalzados” or “Barefoot Franciscans.” Suffice to say, their regimen was very strict and they were very dedicated holy men.

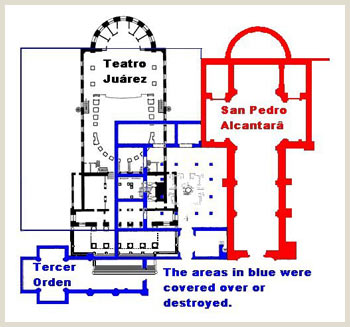

The site of the Convento of San Diego Alcalá which at one time sat alongside the present church of San Pedro de Alcantará is now the site of the Teatro Juárez. At the time that the church and convent were built it was a very poor place to put a structure. No doubt it was put there in part because the Dieguinos themselves were a very poor order. The canyon in which the city of Guanajuato is located is formed by two separate chains of hills which run parallel to each other and in places their bases are separated by only a few dozen yards. It was in exactly such a spot that the Dieguinos located their church and convent. Originally the Guanajuato river flowed leisurely through the canyon between the ranges. Most of the time it was a tranquil little stream but on certain occasions it turned into a raging torrent. The years 1760, 1772, and 1780 were some of those occasions. In those days, before the drainage tunnels were built under the city of Guanajuato, there were various bridges that crossed the bed of the river that flowed along what is now known as Juárez Street. The original site of the Diegan monastery sat in a little bowl formed at the center of four hills through which flowed the river. Every time that there was a flood this little bowl would fill up with water and the result was nearly always destruction and death. After three such episodes in a twenty year period it was determined that something had to be done. The city fathers decided to raise the level of the church and the monastery. The decision to raise the level of the church of San Pedro Alcantará and the adjoining monastery was one of the most striking enterprises in the history of the development of the city of Guanajuato. It must have been a herculean task. Over one half of the cost was paid by the Conde de Valeciano, Antonio de Obregón y Alcocer. He was the owner of the fabulous nearby silver mine and at that time he was the richest man in New Spain. The floors, the walls, and the roofs were raised about 15 to 20 feet and the church received a completely new façade. The amazing thing is that except for the finishing touches the project took only two years to accomplish. It is interesting to note that construction of the Alhóndiga was begun just a few years later. Now let us fast forward to the year 1861. Times had changed quite a bit in Mexico. The battle for independence from Spain had been fought and won and it was now the era of reform. Church property had been confiscated by the state. The city fathers who so obligingly raised the church were no longer living. The new crop of city fathers decided that they wanted a plaza where the courtyard of San Pedro Alcantará was currently located. In order to accomplish their desire they had to tear down the chapel of the Third order of Saint Francis which was part of the church. That was also very significant political act. The “Tercer Orden” or Third Order of Saint Frances was made up of Catholics who did not take the vows of Holy Orders but who followed the strict penitential rules of the Order of Saint Francis in their regular secular lives. The chapel of the Tercer Orden had been reserved exclusively for their use. In those days there was a fierce power struggle going on between the Catholic Conservatives and the Liberals of the Reforma. The Liberal government at the time may have perceived a threat in the presence of the Tercer Orden and fearing that it might become a political club of the religious right they took advantage of the opportunity to tear down the “club house”.

For a time the other parts of the closed down monastery served as a hotel and a stage coach station. In the year 1867, after the execution of Emperor Maximilian, a man named General Florencio Antillón became the governor of the State of Guanajuato. He was a loyal native son, a hero of the army, and last but not least an associate of President Benito Juárez. On the 3rd of August, 1872 it was he who announced that a new theatre was to be built on the site of the old monastery and that it would be a theatre of the first class and serve as a “proof of civilization”. The first stone was laid on may 5th, 1873. The theatre as he envisioned it is not the same edifice that we see today. The first architect was a man named José Noriega who was an associate of General Antillón and collaborated with him on several projects including in that same year the construction in nearby Marfil of the Church of Santa Maria de la Asuncion. This church has a definite gothic look to it and features a clock tower that looks more like a belvedere than a tower and contains a clock made in Germany. Noriega also designed another theatre called the Teatro de la Paz in San Luis Potosí. In 1877 Governor Antillón was unseated by followers of President Porfirio Diaz Mori and the Teatro Juárez project languished until 1891 when it was revamped by an architect named Antonio Rivas Mercado, who by the way, was also the architect who designed the famous Column of Independence in Mexico City. By this time during the Diaz Administration money for opulent public works was flowing like water and the Teatro Juárez final design reflects it.

It is curious to note that the theatre is just about the same size as the church beside it and not only that but the theatre is shaped like the church with an apse, or rounded end at the back. It has no transept, however. A transept is the part of a church that is perpendicular to the nave and forms the arm of a cross when looking down at the floor plan from above. You might say that one was a church built for God and the other a church built for Mammon. When the workers began the foundation for the theatre they stumbled across the original foundation level of the old monastery from 1679 and came up shouting, “Hey, there is a little Pompey down here”. Portions of the old monastery still exist below the street level between the church and the theatre and can be seen today. One of the items pictured with this article is the old well that can also be located in the composite drawing of the monastery perimeter. It is in the center of the square of dots just to the left of the nave of the church. The theatre was more or less completed in 1897 but wasn’t inaugurated until the 27th of October, 1903 when none other than Porfirio Diaz himself came to watch the opening performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida in a theatre named for Diaz’s greatest political rival. That is quite an irony. He could have just as easily had the theatre named after himself, or maybe he thought that it would be one day anyway.

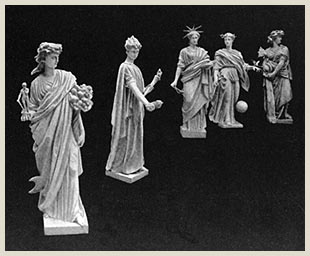

Other than its magnificent columns and bronze lions flanking the front steps one of the most striking features of the theatre are the bronze statues that line the portico reminiscent of St. Peter’s in Rome or Mary Queen of the World Cathedral in Montreal. Instead of being statues of saints as in the aforementioned structures the Teatro Juárez statues bear likeness to Greek mythological figures. They are reported to be the Greek muses, Calliope, Clio, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsicore, Thalia, and Urania. There is only one problem. The Teatro Juárez has only eight statues and there were nine muses. Some people say that Erato was left out and others say it was Euterpe. The statues were made by W.H. Mullins of Salem, Ohio who began making architectural accoutrements in 1882. Among many other things he is famous for his statues of the deer which came to symbolize the John Deere Tractor Company. The statues on the Teatro Juárez are made of pieces stamped from sheet bronze and soldered together. It just so happens that in 1892 Mr. Mullins made some very similar statues for the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. They were supposed to represent the sciences. Perhaps the statues on the theatre are sisters of those statues. That is something that still needs to be checked out. In any case Mr. Mullins must have been quite a guy. He died in 1932 after a very full and fruitful life. One more thing. Whatever became of the Dieguinos? Well, by the last half of the 19th century there was a proliferation of Franciscan missionaries under banners such as the Capuchins, the Riformati, the Recollects, and our own beloved Alcanterines or “Dieguinos”, all marching to the sound of a different drummer. On the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi, October 4th, 1897, Pope Leo the XIII published a papal bull uniting the various branches under one order called the Order of the Friars Minor. So, you see, the Dieguinos didn’t die out. Like good soldiers everywhere they just faded away. Their spirit is still alive and doing the Lord’s work wherever it needs to be done. The next time you see a Franciscan Friar in his brown robes and sandals remember the story San Diego Alcalá, San Pedro Alcantará, and the barefoot Dieguinos of Guanajuato and say a little prayer for all of the followers of St. Francis. As for the Teatro Juárez, it is a truly a rewarding place to visit and hopefully it will stand out as a “proof of civilization” for the people of Guanajuato for years and years to come. Bob Mrotek can be reached by e-mail at bob.mrotek@gmail.com or at info@cityvisions.com.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home | Nature & Human Nature | Automotive Landscape | Artists Portraits | Historic Mexico | Resumé | Contact |